My 5 takeaways from the Human Capital Summit

How has and will technology impact the workforce?

It’s well documented that new technology impacts everyone’s job, no matter what sector or occupation. As the cost of ‘tech’ has fallen, its take-up has accelerated, and with it growing awareness of ongoing and future jobs automation. Yet, perhaps contrary to perception, OECD research shows that 60% of member regions are creating jobs at low risk of automation; evidence that technology creates more jobs than it destroys.

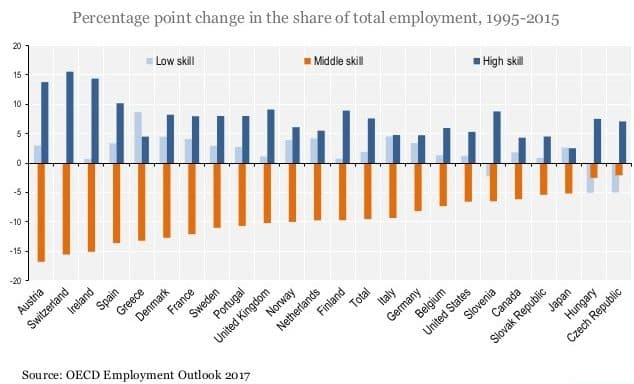

But that change hasn’t happened equally. According to Sylvain Giguère, from the OECD, between 1995 and 2015, developed economies experienced rapid growth in low and high skill jobs, while mid-skill jobs have been in decline. This means there’s arguably a greater need to reskill mid-skilled pockets of our workforce into high-skilled. Yet, historically, the state has tended to direct its resources on upskilling the lowest skilled.

To do this, we need to (a) supply the right skills for the new world of work, (b) upgrade skills of existing workers, and (c) improve the utilisation of skills in the workplace.

That means not only a focus on supply (skilled individuals), but also demand (the right jobs, for the right skills). This is where Digital Jersey as a broker between industry and education can really play a role; working to create industry-led programmes and matching talent with employers.

Technological progress and digitisation are contributing to skills polarisation

What could the future of education look like?

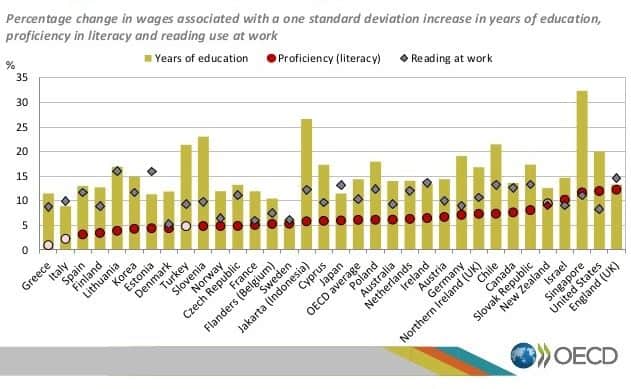

It’s believed compulsory education began in the 1600s, but its scoped has changed dramatically over the generations. In the 1870s, the school leaving age in England was 10, by the late 1940s it was 15, in the 1970s it was 16, and by 2015 the age rose to 18. The length of one’s education has become the single biggest indicator of future wages, and this trend will likely continue as the economy becomes even more knowledge intensive.

As life expectancies continue to rise, islanders will work far past 65; they’ll have multiple careers and their employers will demand ever changing and advancing skills. So, for Jersey, why finish compulsory education at 16? Why not 18, 20, 21, 22? This wouldn’t need to be traditional exam cramming but could include apprenticeships and other work-based training; such as the Digital Leadership Programme.

Effect of education, literacy proficiency and reading use at work on wages

Jersey & Guernsey; adapting education for a digital world of work

The summit was organised by Brighter Futures, a new Guernsey charity which aims to put the island onto a more sustainable path by changing the way we think about lifetime education. It’s a great example of industry-led social philanthropy. The charity is working to fund local students’ education, to create an in depth-labour market analysis, and to organising mid-career MOTs. These workshops will coach and mentor people to help them transition into roles and skills of the 21st century.

At a Government level, the island is consolidating all its higher education provision into the ‘Guernsey Institute’. This will replace the College of Further Education, the Institute of Health & Social Care Studies and the GTA.

In Jersey, the Digital Jersey Academy will be opening this September. The Academy will be the Island’s first Centre of Excellence for digital courses and training. The dedicated facility will work with leading industry partners and education providers to offer a wide range of full-time and part-time digital courses, workshops and events.

Best digital skills solutions and initiatives internationally

Throughout the day, speakers spoke of best practise internationally, where governments and community have taken different approaches both to developing their digital sectors and preparing their communities for the impact of the technology on employment and skills.

Luxembourg’s Digital skills bridge is particularly interesting given similarities in our economies. The scheme is designed to create unity in the process of digital transformation, by offering companies and people free tailored advice and training in digital skills to help employees secure jobs in transition; and thus, minimising any negative consequences of digital transformation.

Singapore’s Skills Future is a long-term national effort to prepare its society for a changing world of work. The government provides resource support to individuals, employers and training institutions. It’s a comprehensive scheme, covering everything from raising awareness and career guidance, to online learning tools, tech focused industry-relevant training programmes and qualifications, and a significant grant programme. The grant programmes alone covering every need, from individual study awards, to place-and-train programmes (e.g. matching people with companies), a S$500 education credit for all over 25s to draw on; and an earn and learn programme where employers receive funds to offset the cost of training.

Kenya moves nearly half its equivalent in gross domestic product (GDP) through mobile phones. The country’s mobile-money system (M-PESA), launched in 2007 by telecoms company Safaricom, sought to address issues of financial inclusion. Effectively, M-PESA enables mobile numbers to act as account number, with users depositing and withdrawing cash at retail outlets. It has improved the standard of living in Kenya by enabling market traders, debt collectors, farmers, cab drivers, etc. to transact online, in turn minimising opportunities for theft, robbery and fraud.

Sweden is home to Europe’s largest tech companies and its capital is second only to Silicon Valley when it comes to the number of “unicorns” (billion-dollar tech companies) per capita. There are multiple reasons for this, but arguably the most credible is its first mover advantage. In the 1990s the state subsidised households to buy PCs, which gave the country the highest level of access to home computers in the world. The rollout of this fibre-optic infrastructure directly financed by the Swedish government has also helped.

The importance of the buzz factor when attracting the millennial generation to the Channel Islands

As expected, comparisons between our islands were drawn regularly. Underpinning this was demography. Like Jersey, Guernsey has an ageing population. By 2025, 50% of Guernsey’s 5,500 strong public workforce will have retired. For our economies to succeed, it’s vital that the islands attract ‘younger’ global and local talent. This was stressed by all speakers. And yet, our islands’ population policies have gone in opposite directions, with Jersey’s growing, and Guernsey’s stagnating.

Panellists spoke, enviously, of St Helier having an attractiveness and buzz for young professionals that St Peter Port lacks. Stories of young professionals, families and newly qualified financiers uprooting and moving to Jersey was said to be common.

This is likely accelerate with demographic changes. By 2025, 75% of the globe’s workforce will be millennials, a generation that priorities work life balance. Indeed, for future generations, the interplay between the perceived attractiveness of a location, and that of the businesses that cluster within it will only become stronger.

With this in mind, governments and industry will need to take a complete view of talent attraction, from population policy, to training opportunities and (obviously) ‘Friday night’ amenities.

Check out full details of speakers and more from the event here: https://py1fwl.attendify.io/

Find out more about the future of education and digital skills in Jersey.

James Linder

Policy Manager at Digital Jersey